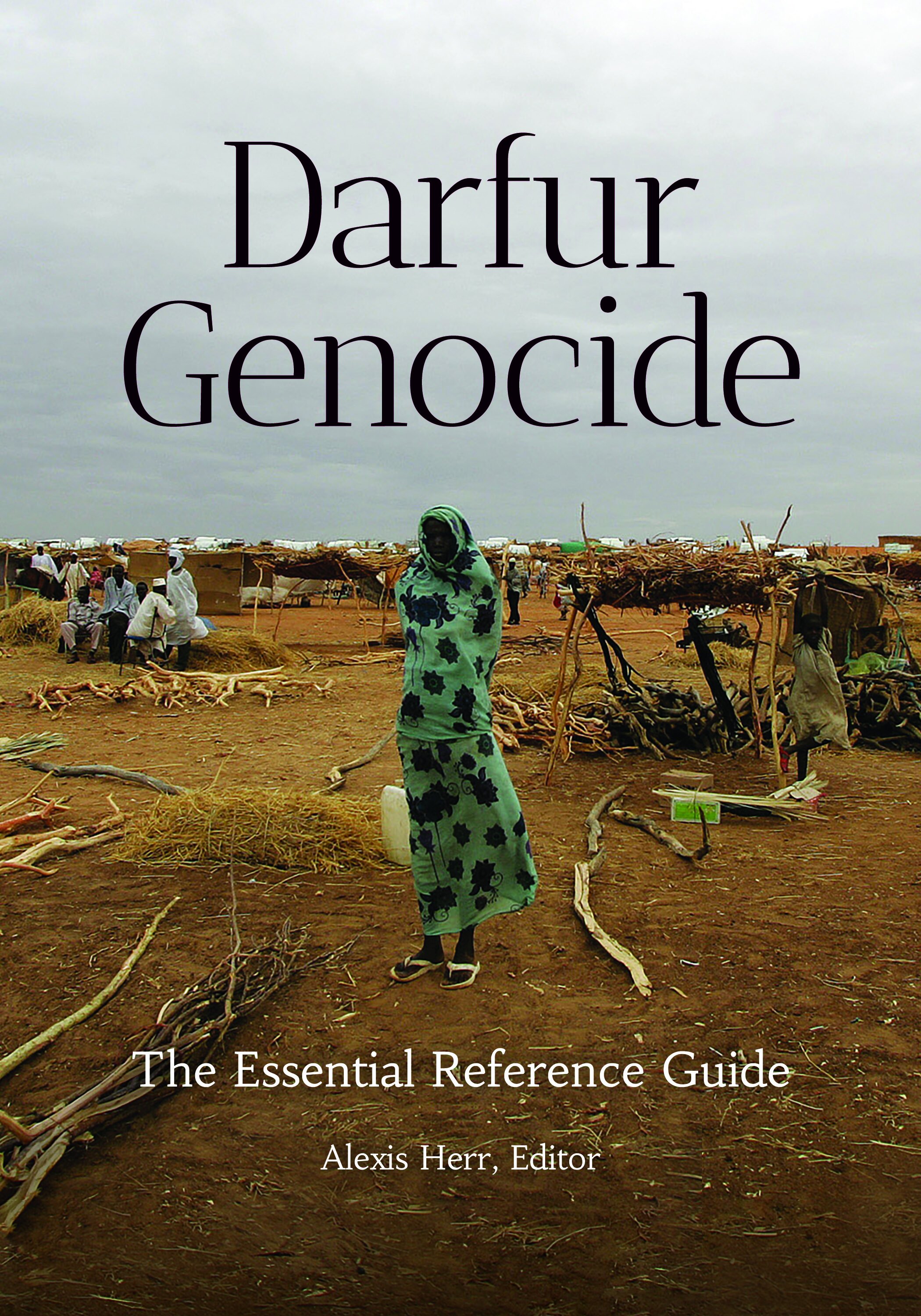

Preface to my newest volume on the Darfur Genocide

For the past year I have been working on a reference guide for students of the Darfur Genocide and it was released earlier this year. It is my pleasure to share with you all the preface to this new work!

All genocides have a past, present, and future. In our quest to learn about the Darfur Genocide, it is imperative to remember this simple truth in order to avoid the common error of mistaking dates as definitive, statistics as representative, and accumulated knowledge as understanding. Ultimately, any true study of genocide requires its students, myself included, to grapple with a reality that is too tangled to unwind and too dark to fully illuminate.

When Western media outlets first reported on the eruption of violence in the Darfur region of Western Sudan in 2003, they attempted to simply describe the seed of the conflict as racial violence so that their readers could comprehend the confrontation that U.S. secretary of state Colin Powell would later call a genocide. Journalists reported that “Arabs” were killing “Africans,” thus framing the violence as racially driven.

The explanation of racial hatred was not a foreign concept for Westerners, even if Darfur and Sudan required an internet search to locate. Ever since images of the Holocaust (1939–1945) entered into our collective consciousness through print and visual media, the notion of genocide has had a strong association with the attempted annihilation of an entire people. The killing of the Tutsis by the Hutus in Rwanda (1994) reinforced this image of racially or ethnically motivated genocide. So, the explanation of Darfur as a genocide motivated by racial hatred brought familiar clarity for those in the West about an otherwise distant conflict.

But this oversimplification allowed for uninformed assumptions about a people and a place, due in part to the broader global context. The world had been forever changed just two years before the genocide began in Darfur, when al-Qaeda terrorists launched an attack on the West on September 11, 2001, murdering nearly 3,000 people from more than fifty-seven countries in a single day. For many years, Osama bin Laden, the mastermind of the September 11 attacks, was painted as the poster child for Islamic extremism and the so-called Arab world was depicted as the greatest enemy of Western Christianity and democracy.

Western confusion about Sudan was made worse by the fact that bin Laden had a history in the country, having spent years nurturing his nascent terrorist group there. Sudanese president Hassan al-Turabi had welcomed bin Laden to the country in December 1991, and as he set up terrorist training camps, Turabi intensified his own Islamic extremism through his party, the National Islamic Front (NIF). As one scholar has aptly explained, “if al-Qaeda was not actually born in Sudan, it certainly developed its modus operandi in the bosom of al-Turabi’s Islamic revolution” (Crockett 2010: 122–123). Thus, when reporters wrote in 2003 that Sudanese “Arabs” were murdering “Africans,” many saw the conflict through the lens of Western Islamophobia.

For some, the category of “Arab” was interpreted as “Muslim” and violence against “Africans” as religiously motivated. Thus, despite the fact that nearly all the perpetrators and the victims of the Darfur Genocide practice Islam, some well-meaning people reading about violence in Darfur assumed the conflict was a religiously motivated genocide. Such assumptions expose one of the weaknesses of studying violent acts within the temporal vacuum in which we live. In our rush to understand that which defies simple explanation, we take shortcuts. This approach, however, ultimately limits our ability to gain the understanding needed to effectively upend and prevent genocide.

In reality, the Darfur Genocide is complex and multifaceted. Studying Darfur, like all genocides, requires us to continually question our assumptions because, ultimately, we should never accept the answer that hatred alone is the root of all genocides. Such a conclusion is far too simplistic and in overreaching it ignores the steps that transform difference into division and neighbors into enemies. Nearly all the victims and perpetrators of the Darfur Genocide were born in Africa and nearly all involved practice Islam. To claim that the Darfur Genocide is motivated by Arabs killing Africans, or even more erroneous, Muslims killing Christians, belies Sudan’s rich and long history of identity, tradition, and culture.

The Darfur Genocide is far more than a sixteen-year conflict driven by racial hatred. Curated to avoid such tropes, this volume includes entries that help us widen our gaze, take into consideration historical events that inform identity politics in Sudan, and debate key questions about the genocide. In the Introduction, readers will gain a thoughtful overview of the history, conflict, and outcomes of the genocide and in so doing develop the intellectual toolset to study the Darfur Genocide in greater detail. To conclude this volume, we have reproduced nine primary source documents that allow readers to explore what the international community knew when the killings began, how the United Nations and its member states responded, and read speeches from John Garang, who championed the fight for South Sudan’s independence and advocated for peace in Darfur. Lastly, this volume includes articles from five leading genocide scholars who take different positions when answering the following questions: Is the conflict in Darfur a just case for intervention? What was the primary cause of the Darfur Genocide?

The wealth of entries, arranged in alphabetical order for ease of use, go even deeper into the history to enhance a learner’s comprehension of the genocide. For example, in addition to perceived ethnic divisions (see Dinka; Fur; Massalit; Zaghawa), it is helpful to consider environmental (see Famine of 1984–1985), colonial (see British Involvement in Darfur; Egyptian Involvement in Darfur; Religion), and political developments (see Bashir, Omar Hassan Ahmad al-; Darfur Development Front; Justice and Equality Movement; Khartoum; National Islamic Front; South Sudan; Sudanese Civil Wars) that stratified tribal and regional identities. Likewise, any effort to study the Darfur Genocide is significantly enriched when contemplated in conjunction with the Sudanese civil wars, which help to explain, in part, why most of the international community and the United Nations did not refer to the killings in Darfur as genocide even when the United States did (see Annan, Kofi; Comprehensive Peace Agreement; Denial of the Darfur Genocide; Garang, John; Kiir, Salva; Nuba; Religion; South Sudan; Sudanese Civil Wars).

This work also highlights the many efforts of African and international governments, coalitions, celebrities, and grassroot organ- izations to stop the killing of Darfurians and alleviate the suffering of refugees. The inter- national community experimented with new peacekeeping efforts (see African Union Mission in Sudan; Lost Boys and Girls of Sudan; United Nations–African Union Mis- sion in Darfur; United Nations Mission in Sudan) and endeavored to gather accurate information about the killings despite Sudanese president Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir’s best attempts to block humanitarian access (see Amnesty International; Coalition for International Justice; Darfur Atrocities Documentation Project; Enough Project; Satellite Sentinel Project; Save Dar- fur Coalition). Celebrities also used their fame to shine a spotlight on the killing, and in so doing helped the Darfur Genocide get more attention than any other modern atroc- ity (see Cheadle, Don; Clooney, George; Damon, Matt; Farrow, Mia; Jolie, Angelina; Kristof, Nicholas; McGrady, Tracy; Prender- gast, John).

And yet, despite the press coverage, research, and international involvement in peace efforts, the killing in Darfur contin- ues, which is why recent events in Sudan are all the more remarkable. When thou- sands of citizens gathered in Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, in 2018 to protest rising food prices, calls for food subsidies quickly changed into chants to remove Bashir from power. Since Bashir overthrew the Sudanese government almost thirty years ago, the condition of human rights in Sudan has declined rapidly. Under his leadership, mil- lions have died in conflicts described as genocide, civil war, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and terrorism. Millions more have abandoned their homes to escape the violence. Prior to South Sudan achiev- ing independent statehood in 2011, Sudan held the somber distinction of having more internally displaced persons than any other country in the world with nearly 4.3 million Sudanese displaced by decades of conflict.

While foreign leaders, the United Nations, and celebrity clout could not remove this dic- tator from his throne, the manifest force of a civilian population unwilling to backdown has succeeded. The Sudanese Professional Association, an alliance of doctors, educa- tors, scientists, lawyers, and other such lay leaders, has rallied a million people to peace- fully assemble and demand a democratic Sudan. On April 14, 2019, Bashir was deposed and arrested. Currently, Sudanese civilians continue to gather in Khartoum to press the military powers that have assumed the role of government in the interim to cre- ate a power sharing agreement with the people. Though Sudan’s past is full of pain, its present is one of resolve and hope. Its future is now up to the people of Sudan.

I am incredibly grateful to have worked on this project with ABC-CLIO, and I am thankful for its proven commitment to geno- cide education. In particular, Padraic (Pat) Carlin, a former managing editor at ABC- CLIO, has been a great supporter of this work and our shared frustration over the ongoing genocide in Darfur helped motivate the publication of this reference guide. Genocide activism can take many forms and there are endless ways to get involved in upending atrocity like that in Darfur. This is our contribution to the fight against geno- cide. It is our hope that in learning more about Darfur, we will be more prepared to prevent genocide and support its victims now and in the future.

And as always, I am thankful for the support of my husband, Shayle Kann, and my friends and family for encouraging me to keep learning and teaching about atrocities, even when it keeps me up late at night.

Alexis Herr